My First Visit To My Birthplace, The Village Neret Near Lerin in Aegean

Macedonia

By Atanas Strezovski

printable

version

printable

version

I

am Atanas Strezovski, an Australian citizen and passport holder. In

July 2003, while on holiday in Europe, I decided to visit my birthplace

to see my relatives and friends and to be present at the wedding of

the daughter of aunty, Georgiou Elefterija.

I

am Atanas Strezovski, an Australian citizen and passport holder. In

July 2003, while on holiday in Europe, I decided to visit my birthplace

to see my relatives and friends and to be present at the wedding of

the daughter of aunty, Georgiou Elefterija.

While in Bitola, the Republic of Macedonia, I had received an invitation,

written using the Greek alphabet to make Macedonian words. The letter

said that I would be welcome “dear nephew” to attend the wedding

of Hrisula and Atanasios and that they would wait “with warm heart”

for me to arrive.

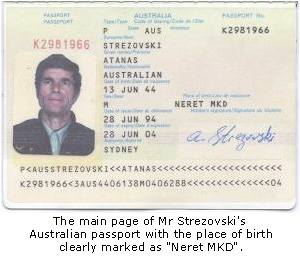

On my first attempt to return to Greece for a visit in August 1994

I had been denied entry - the border official told me this was because

my passport had my birthplace as “Neret” and the country as

“MKD”. Neret is the original Macedonian name for my village,

and MKD is the international abbreviation for Macedonia. However, after

the Balkan Wars the region became part of Greece and the village was

renamed into the Greek “Polipotamos”. The border official

said that there was “no way” I could enter Greece while the

terminology “Neret” and “MKD” were in my passport.

On this occasion, because I had the invitation, I had a small hope

that the Greek authorities would permit me to enter Greece when I arrived

at the border checkpoint at Medzitlija. To encourage me, my mother,

Paraskeva, who was also born in Neret but now lives in Bitola, had said

to me that many people had been let into Greece because they had such

an invitation. But I later realized that the invitation was irrelevant

to the Greek authorities.

I made a deal with a Macedonian taxi driver that he would take me to

the village Neret for 25 euros.

We

set out at 8.30 am. The whole time I was afraid that they would not

let me into Greece, as I know that many Macedonians born in Aegean Macedonia

(now called northern Greece) have been wiped out from the records forever

by the Greek authorities.

We

set out at 8.30 am. The whole time I was afraid that they would not

let me into Greece, as I know that many Macedonians born in Aegean Macedonia

(now called northern Greece) have been wiped out from the records forever

by the Greek authorities.

Despite the history and my own experience in 1994, I kept my small

hope that they would let me enter. On the way, the owner of the taxi

said that many hundreds of Macedonians with Australian and Canadian

passports had been denied entry at the border simply because their birthplace

was written under the original Macedonian name, for example “Buf,

Makedonia”. According to the taxi driver, the Greek Government

does not want to see Macedonian names and that is why they turn people

back. The Government wants to see these toponyms written only under

the new Greek names with which they had Christened them.

He said that when the Macedonians were denied entry they became very

unhappy and that as a taxi driver he was also unhappy as the passengers

paid for their journey but had not reached their destinations. What

the Greeks are doing is very unfair, he said, but they are very powerful

internationally and what can the Macedonians do? He then added that

he has two Greek border officers who are good friends of his and that

if one of them is on duty there is a small possibility that I could

pass through. Otherwise there would be no chance at all, he said.

About 9 am we reached the check point, Medzitlija. He told me to wait

in the taxi and he would test the ground for me. A few minutes later

he returned and said it was successful.

When I saw the stamp in my passport, I was surprised that I would be

allowed to pass the border, as I could clearly remember not being allowed

to pass through in 1994. I could not believe the situation. I was overjoyed.

As soon as we started the car, I said to the taxi driver “The

ice is broken, the times are softer, and even the Greeks can see that

the Macedonians are people too. This is probably because of criticism

and pressure from human rights organizations and the European politicians

and community.” The young taxi driver said “Do not be so happy

until the job is done and we reach your village.” The driver said

that although he had been to many villages, this was the first time

he was going to Neret. We would need to ask directions from somebody

and, as there were a lot of Greek agents in plain clothes, to be on

the safe side we would need to ask in the Greek language and to ask

for the village using its Greek name. “Pujse to Polipotamos”

he said to me in Greek to show me how, as I was on the footpath side

of the car.

And that is what happened. When we met a women, I said the above words

and she answered something in Greek which I did not understand. But

the taxi driver told me even if I do not understand what she is saying,

she was showing with her hand that we need to turn right at the T junction.

We continued on for another 10 minutes. But to ensure we were going

in the right direction, we stopped again and asked a man who was plastering

a house - using the same Greek words above. His short answer - in perfect

Macedonian - was that we were on the road to the village Neret (“pa

Vie patuvate za selo Neret”). With a similar short reply - also

in Macedonian - I said to him with a smile “Yes, we are going there.”

("Da, tamu odime.”) He gave us precise directions. “Turn

left at the third bridge. It is the last village. You cannot miss it.”

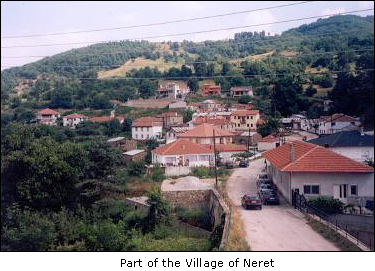

In 15 minutes we arrived at the village Neret. At once I was greeted

by my relatives, my aunty Elefterija and my cousins Dimitrios and Vasili

Tolis.

The

wedding was underway when we arrived. The band played Macedonian and

Greek music. But there was only music - no singing. Even well known

Macedonian national songs, such as “Mariche Le Lichno Devojche”

(Maria You Pretty Girl) were only played by the band but no one sang

to the music.

The

wedding was underway when we arrived. The band played Macedonian and

Greek music. But there was only music - no singing. Even well known

Macedonian national songs, such as “Mariche Le Lichno Devojche”

(Maria You Pretty Girl) were only played by the band but no one sang

to the music.

Until 4 pm the ceremonies were only in the centre of the village. Around

3 pm I went to the church to speak with the priest. There was no sign

of the name of the church - not in Macedonian nor in Greek. I asked

the priest but he refused to answer. He seemed frightened. I asked one

of the guests near me “What is the name of this church?” The

lady replied “Sv Bogorodica” (St Mary). I asked why there

is no name on the church? Why it is blank? She said “We know the

name”. When I asked the priest if the church is called Sv Bogorodica

he said “Yes” in Macedonian, but made no further comment.

But the service in the church was entirely in the Greek language.

Outside

the church and in the village, when there were no Greeks present, the

people generally spoke Macedonian, so my impression was that the Macedonian

language at least is no longer forbidden. However, it is a shame that

there is no Macedonian school and that the Macedonian language is not

used or taught at school.

Outside

the church and in the village, when there were no Greeks present, the

people generally spoke Macedonian, so my impression was that the Macedonian

language at least is no longer forbidden. However, it is a shame that

there is no Macedonian school and that the Macedonian language is not

used or taught at school.

That evening in the nearby town of Lerin, in the hall where the wedding

celebrations continued, the band played Macedonian music but the words

were sung in the Greek language.

After the wedding we returned to Neret and I stayed with my cousin

Dimitrios.

The next day I awoke about 10 am. I was alone in the house. I looked

at the photograph albums, which my cousin had already pointed out to

me.

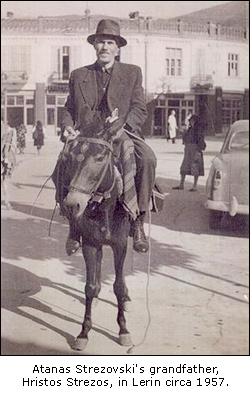

Most

of the photographs were of my relatives, and I saw photographs of my

dead grandfather, Hristos Strezos. I also saw photos of his son, my

uncle, Kosta Strezov, who now lives in the town of Burgas in Bulgaria.

It was Kosta who had originally told me about this wedding and suggested

I try to enter Greece to attend. Kosta had previously not been allowed

to enter Greece and so on this occasion had not tried to enter to attend

the wedding.

Most

of the photographs were of my relatives, and I saw photographs of my

dead grandfather, Hristos Strezos. I also saw photos of his son, my

uncle, Kosta Strezov, who now lives in the town of Burgas in Bulgaria.

It was Kosta who had originally told me about this wedding and suggested

I try to enter Greece to attend. Kosta had previously not been allowed

to enter Greece and so on this occasion had not tried to enter to attend

the wedding.

I also saw a photograph of my grandfather’s other son, my father,

Giorgi Strezovski. I was in the photograph, a child of about four sitting

on his knee. The photo was taken in Bitola in about 1948. I was born

in 1944 and my family had left Neret and gone to Bitola while I was

a baby. My father was a patriot. He had told my mother that if we stayed

in the village we would become Greeks but if we left we would have a

chance to remain Macedonians. Many other Macedonians in Greece had felt

the same.

I

believe that as a Macedonian intellectual my father was persecuted by

Serbian nationalists. My father was a professional musician, a clarinet

player and composer, but in the photograph he was wearing a Yugoslav

army uniform. Because of the split between Tito and Stalin, he was imprisoned

for about three years in Serbia during the time of the “Informbiro”.

His health deteriorated through maltreatment, and the prison doctor

diagnosed that he would soon die. They let him free so that he would

not die in the prison hospital. From Serbia he moved to Bitola and then

Skopje but no doctor could help him and he passed away.

I

believe that as a Macedonian intellectual my father was persecuted by

Serbian nationalists. My father was a professional musician, a clarinet

player and composer, but in the photograph he was wearing a Yugoslav

army uniform. Because of the split between Tito and Stalin, he was imprisoned

for about three years in Serbia during the time of the “Informbiro”.

His health deteriorated through maltreatment, and the prison doctor

diagnosed that he would soon die. They let him free so that he would

not die in the prison hospital. From Serbia he moved to Bitola and then

Skopje but no doctor could help him and he passed away.

I

also saw my mother, Paraskeva Strezovska, with her sons Lenin and myself,

Atanas, photographed in Ohrid, although I do not know in what year.

I was about 10 years old.

I

also saw my mother, Paraskeva Strezovska, with her sons Lenin and myself,

Atanas, photographed in Ohrid, although I do not know in what year.

I was about 10 years old.

I also saw a photograph of myself as a Serbian soldier in the Yugoslav

National Army. The photo was dated 25.10.1964.

I also saw a photograph of my cousin, Toli Dimitrios, dressed as a

Greek ‘Evzon” guard.

At my request, my cousin, Vasili Tolis, took me to the monastery Sv

Luka, where there are the graves of my relatives, including that of

my grandfather Hristos Strezos, who died in 1975. The family believes

this was from beatings by Greek agents whom the Macedonians call “andarti”.

We believe the reason is that he received a letter from Australia which

was addressed to Risto Strezovski and not Hristos Strezos, the Greek

version of his name.

I

also saw the graves of my cousin Hristos Tolis and his wife Fane Filippoi,

for whom I lit candles.

I

also saw the graves of my cousin Hristos Tolis and his wife Fane Filippoi,

for whom I lit candles.

Again, in this monastery also, I could see no writing to indicate its

name.

In the village cafe, I met with a group of Macedonians who spoke in

Macedonian. I joined the group and they accepted me. I told them I was

born in the village but had left as a baby and this was the first time

I had come back in 59 years.

They

asked to see my passport and when they saw written the word “Neret”

they were surprised and said how good it was that I could successfully

enter Greece. I told them the story of the taxi driver.

They

asked to see my passport and when they saw written the word “Neret”

they were surprised and said how good it was that I could successfully

enter Greece. I told them the story of the taxi driver.

They mentioned that even a letter which has Macedonian script or names

and surnames is not delivered. They believed such letters are returned

to sender but I believe they could be kept by the Greek authorities

or even destroyed.

After three days the time came for me to leave for Bitola. Around 5

pm I said my goodbyes to my relatives, and my cousin Vasili took me

to the border at Medzitlija.

On the way my cousin said he would bring me to Lerin to see my grandfather’s

old shop where he practised as a tailor. My father also worked there

as a boy before he became a musician. The shop has been closed since

the late 1920s or early 1930s when my grandfather travelled to Australia

to look for work. The shop looks as it was then and I took several photographs.

We

started again for Bitola and my cousin said to me “Oh cousin, Tanase,

if you had stayed here instead of emigrating you would have a house

in Neret, a farm in Neret, and a shop in Lerin. Because your family

was not here your grandfather Hristos gave everything to us and made

us promise we would not sell the shop to anyone.” I did not have

a comment to this, except to say “Good luck to you for your inheritance

and may you have a happy life. If I have another chance in my life time

I will come back again. All I want is for us to be healthy and happy.”

We

started again for Bitola and my cousin said to me “Oh cousin, Tanase,

if you had stayed here instead of emigrating you would have a house

in Neret, a farm in Neret, and a shop in Lerin. Because your family

was not here your grandfather Hristos gave everything to us and made

us promise we would not sell the shop to anyone.” I did not have

a comment to this, except to say “Good luck to you for your inheritance

and may you have a happy life. If I have another chance in my life time

I will come back again. All I want is for us to be healthy and happy.”

At the border, I wanted to make my farewells and to continue alone,

in case there was some problem at the check point which I did not want

my cousin to suffer. But my cousin said he would take me to the Macedonian

border.

At that moment I had a feeling that something unexpected could happen.

But my cousin insisted with the words “Don’t worry. I was

an evzon guard here and everyone knows me.”

When I gave my passport to the Greek official, he opened it and carefully

read every part. He looked aghast and said “Selo Neret”.

As he said the Macedonian word “Selo”, which is nowhere in

the passport, I immediately realized that he may be of Macedonian background.

The possibility that he could be reminded me of a “Janichar”,

a Turkish word from the Ottoman period that meant a Macedonian child

who had been confiscated from their parents and raised as a soldier

to kill Macedonians.

I got a feeling that I would have a problem. I was mostly worried about

my cousin Vasili as I would be returning to Australia but he would remain

there.

The official asked me in Greek “What is Neret?” and what

is “MKD?”. I shrugged my shoulders and as I do not speak Greek

I answered to my cousin in Macedonian so that he could translate “I

do not know”, even if I did know.

He

rolled the passport nervously in his hands. He made a phone call and

looked up some books, ostensibly to find out what “Neret”

and “MKD” mean, although I believe he already knew what they

meant. I waited for about an hour at the counter. Meanwhile a number

of people with Greek passports passed through trouble-free at the same

window. As I waited on my feet I began to feel I was being punished.

The officer held his head with both hands and looked as if he could

not believe what he was reading. I wondered how a person including myself

could have passed the check point and not have been checked properly.

Clearly there had been some sort of “error” by the officer

who had allowed me to enter Greece. I felt that the officer could get

into serious trouble for allowing me in, and I felt sorry for him as

what he had done was right from a humanitarian point of view. Meanwhile

the officer I stood before still could not believe what he saw and continued

to fidget with the passport. Finally he asked me when and how I entered

Greece and who had let me in? My answer through my cousin who translated

was that I did not know which officer it was but that I passed through

the same road on which I now wished to leave. I told him the date and

the time and that now two days later I am waiting patiently to leave

as relatives of mine were on the Macedonian side of the border with

a car.

He

rolled the passport nervously in his hands. He made a phone call and

looked up some books, ostensibly to find out what “Neret”

and “MKD” mean, although I believe he already knew what they

meant. I waited for about an hour at the counter. Meanwhile a number

of people with Greek passports passed through trouble-free at the same

window. As I waited on my feet I began to feel I was being punished.

The officer held his head with both hands and looked as if he could

not believe what he was reading. I wondered how a person including myself

could have passed the check point and not have been checked properly.

Clearly there had been some sort of “error” by the officer

who had allowed me to enter Greece. I felt that the officer could get

into serious trouble for allowing me in, and I felt sorry for him as

what he had done was right from a humanitarian point of view. Meanwhile

the officer I stood before still could not believe what he saw and continued

to fidget with the passport. Finally he asked me when and how I entered

Greece and who had let me in? My answer through my cousin who translated

was that I did not know which officer it was but that I passed through

the same road on which I now wished to leave. I told him the date and

the time and that now two days later I am waiting patiently to leave

as relatives of mine were on the Macedonian side of the border with

a car.

The officer seemed exhausted from asking me the same questions over

and over and did not know what else to ask me. Finally he gave back

the passport. I thanked him and quickly left the building.

As I opened the car door and was about to sit, I saw an officer, a

large man with a uniform, coming towards me. Unlike the other officer,

he had a pistol on his hip. He spoke in rapid Greek, of which I could

only understand the word “passport”. Immediately I understood

the problem and gave him the passport. He entered the checkpoint office

from which I had just left.

I waited on the footpath for about seven minutes. The large officer

then returned and gave me the passport. I thanked him in English.

We entered the car and left immediately for the Macedonian border.

I wondered why the large officer had taken my passport when the first

officer has already cleared me to leave. As we were driving I opened

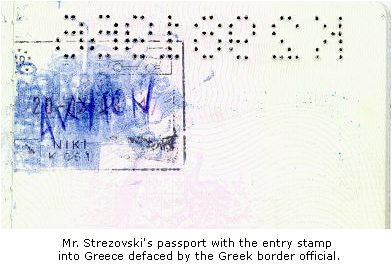

the passport to see if there had been any changes. I saw that the stamp

for my entry into Greece had been badly smudged with blue ink so that

the Greek words were no longer identifiable. There was also some new

handwriting - the word “AKYION”, presumably a Greek word.

I also noticed that there was no stamp for my exit.

In

those moments I asked myself what all this meant? Whether that by destroying

my entry stamp it made it look as if I had entered Greece illegally,

perhaps by jumping the fence or crossing some farmland or bush etc,

rather than having passed through the checkpoint? Was that the reason

for defacing the passport - to destroy the evidence that I entered Greece

legally? However I did not believe that they could fully destroy the

evidence of my legal entry as surely the information would have been

entered in their computer system?

In

those moments I asked myself what all this meant? Whether that by destroying

my entry stamp it made it look as if I had entered Greece illegally,

perhaps by jumping the fence or crossing some farmland or bush etc,

rather than having passed through the checkpoint? Was that the reason

for defacing the passport - to destroy the evidence that I entered Greece

legally? However I did not believe that they could fully destroy the

evidence of my legal entry as surely the information would have been

entered in their computer system?

I decided I would take action to make these events known to various

Macedonian human rights organizations in Bitola and Sydney and to the

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs in Canberra.

A year later I am still asking myself - what is the real problem? Is

it that I entered Greece under my original Macedonian name and surname;

is it that I entered Greece under the original Macedonian name of my

village - Neret, instead of the Greek Polipotamos as they have renamed

it; or is it that I entered Greece with the international abbreviation

for Macedonia - MKD. I think it is that any or all three of the above

would signify official recognition for the Macedonian people and country.

Sydney, June 30, 2004

See also: Photo: Strezov family

Mr Strezovski features in the song Bolka

za Neret.

Source: www.pollitecon.com